Art is capable of expressing, and of making visible, man’s need to go beyond what he sees; it reveals his thirst and his search for the infinite.

Pope Benedict XVI, General Audience

August 31, 2011

Yesterday from his residence at Castel Gandolfo, the Holy Father delivered an inspiring address on the theme of beauty as a way to God. The full text of his brief meditation is just below, but before I leave you to enjoy it, I would simply like to point out to those participating in our Virtual Summer Circle of Thomistic Studies, the way in which Pope Benedict’s theme resonates with what Maritain has to say in Chapter V of Art and Scholasticism.

On p. 31* Maritain recalls the etymology of the Greek word for beauty, to kalon, which derives from the verb, “to call.” The beautiful is a call—ultimately a call by God to the human person “wounded,” as the pope puts it in his address, by the beautiful work of art. He then quotes St. Thomas Aquinas: “the beauty of anything created is nothing else than a similitude of divine beauty participated in by things.”

In his address Pope Benedict focuses on beautiful works of art, and Maritain adds the point that everything beautiful serves as a point of contact with the Creator, who is Beauty Itself.

Pope Benedict observes: “Art is capable of expressing, and of making visible, man’s need to go beyond what he sees; it reveals his thirst and his search for the infinite. Indeed, it is like a door opened to the infinite, [opened] to a beauty and a truth beyond the every day.”

What Pope Benedict says next, however, raises a question. He writes: “But there are artistic expressions that are true roads to God, the supreme Beauty — indeed, they are a help [to us] in growing in our relationship with Him in prayer. We are referring to works of art that are born of faith, and that express the faith.”

Now, before this passage he says that beautiful works of art open us to the infinite. Then he says, “But there are artistic expressions that are true roads to God, the supreme Beauty”—these expressions being properly Christian art. I don’t take the Holy Father to be saying that art made by non-Christians does not lead us to the infinite, and thus in some sense to God. I take it that he’s saying that any work of beauty can potentially lead to an experience of God, but that properly Christian art can lead one to a specifically Christian conversion, as well as deepen the experience of Christian prayer.

Let me know how you see it after reading the full text of the address.

* Page numbers refer to Art and Scholasticism and The Frontiers of Poetry, trans Joseph W. Evans (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1974).

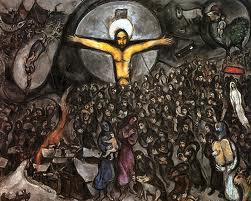

P.S. The image at the top is of "Exodus" by Marc Chagall, who is mentioned in the pope's address.

Full Text of Pope Benedict’s General Audience Address

August 31, 2011

Dear brothers and sisters,

On several occasions in recent months, I have recalled the need for every Christian to find time for God, for prayer, amidst our many daily activities.The Lord himself offers us many opportunities to remember Him. Today, I would like to consider briefly one of these channels that can lead us to God and also be helpful in our encounter with Him: It is the way of artistic expression, part of that “via pulchritudinis” — “way of beauty” — which I have spoken about on many occasions, and which modern man should recover in its most profound meaning.

Perhaps it has happened to you at one time or another — before a sculpture, a painting, a few verses of poetry or a piece of music — to have experienced deep emotion, a sense of joy, to have perceived clearly, that is, that before you there stood not only matter — a piece of marble or bronze, a painted canvas, an ensemble of letters or a combination of sounds — but something far greater, something that “speaks,” something capable of touching the heart, of communicating a message, of elevating the soul.

A work of art is the fruit of the creative capacity of the human person who stands in wonder before the visible reality, who seeks to discover the depths of its meaning and to communicate it through the language of forms, colors and sounds. Art is capable of expressing, and of making visible, man’s need to go beyond what he sees; it reveals his thirst and his search for the infinite. Indeed, it is like a door opened to the infinite, [opened] to a beauty and a truth beyond the every day. And a work of art can open the eyes of the mind and heart, urging us upward.

But there are artistic expressions that are true roads to God, the supreme Beauty — indeed, they are a help [to us] in growing in our relationship with Him in prayer. We are referring to works of art that are born of faith, and that express the faith. We see an example of this whenever we visit a Gothic cathedral: We are ravished by the vertical lines that reach heavenward and draw our gaze and our spirit upward, while at the same time, we feel small and yet yearn to be filled.

Or when we enter a Romanesque church: We are invited quite naturally to recollection and prayer. We perceive that hidden within these splendid edifices is the faith of generations. Or again, when we listen to a piece of sacred music that makes the chords of our heart resound, our soul expands and is helped in turning to God. I remember a concert performance of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach — in Munich in Bavaria — conducted by Leonard Bernstein. At the conclusion of the final selection, one of the Cantate, I felt — not through reasoning, but in the depths of my heart — that what I had just heard had spoken truth to me, truth about the supreme composer, and it moved me to give thanks to God. Seated next to me was the Lutheran bishop of Munich. I spontaneously said to him: “Whoever has listened to this understands that faith is true” — and the beauty that irresistibly expresses the presence of God’s truth.

But how many times, paintings or frescos also, which are the fruit of the artist’s faith — in their forms, in their colors, and in their light — move us to turn our thoughts to God, and increase our desire to draw from the Fount of all beauty. The words of the great artist, Marc Chagall, remain profoundly true — that for centuries, painters dipped their brushes in that colored alphabet, which is the Bible.

How many times, then, can artistic expression be for us an occasion that reminds us of God, that assists us in our prayer or even in the conversion of our heart!

In 1886, the famous French poet, playwright and diplomat Paul Claudel entered the Basilica of Notre Dame in Paris and there felt the presence of God precisely in listening to the singing of the Magnificat during the Christmas Mass. He had not entered the church for reasons of faith; indeed, he entered looking for arguments against Christianity, but instead the grace of God changed his heart.

Dear friends, I invite you to rediscover the importance of this way for prayer, for our living relationship with God. Cities and countries throughout the world house treasures of art that express the faith and call us to a relationship with God. Therefore, may our visits to places of art be not only an occasion for cultural enrichment — also this — but may they become, above all, a moment of grace that moves us to strengthen our bond and our conversation with the Lord, [that moves us] to stop and contemplate — in passing from the simple external reality to the deeper reality expressed — the ray of beauty that strikes us, that “wounds” us in the intimate recesses of our heart and invites us to ascend to God.

I will end with a prayer from one of the Psalms, Psalm 27: “One thing have I asked of the Lord, that will I seek after; that I may dwell in the house of the Lord all the days of my life, to behold the beauty of the Lord, and to inquire in his temple” (Verse 4). Let us hope that the Lord will help us to contemplate His beauty, both in nature as well as in works of art, so that we might be touched by the light of His face, and so also be light for our neighbor. Thank you.